A conversation between Paul Maheke and Louis Chude-Sokei

LOUIS CHUDE-SOKEI: How does the body work in your practice?

PAUL MAHEKE: After graduating from my Masters in Paris in 2011, I was mostly working with drawings and installation when I started to physically perform gestures in public space. These gestures were always conducted anonymously and through them there was the desire to just disappear. My drawing practice was about self-portraiture and looking at the body as a vessel for history and embodied knowledge. I took the opposite approach with my performance work where I wanted to completely remove the public’s understanding of my body from my work. I wanted to explore the idea of an artwork that may not be seen or experienced by people in a complete way.

LCS: In a recent conversation with choreographer Bill T. Jones, I admitted my own discomfort with dancers because their ease with their visibility in a public space can make others uncomfortable as they reflect on their own bodies in that space. In art, music, culture, and literature, discomfort is often connected to resistance, and for an audience, to how we grow and expand. When I first encountered your work, I saw it as hypervisibility vis-à-vis erasure. However, the desire to disappear that you have stated is more complex. As writers, scholars, and artists of color, we deal with silencing and marginality, so what does it mean to play with erasure? Erasing yourself through visible gestures is seemingly a contradiction.

PM: I always need a level of abstraction. When I first made drawings, they were barely visible on paper and there was a strong act of resistance against the appetite for black bodies, brown bodies, marginalized identity. Édouard Glissant speaks about it beautifully with the concept of “opacity,” and I wanted to explore something that would go further through the idea of “translucency.”1 I started to think about it with my good friend Nkisi (Melika Ngombe Kolongo) and the choreographer Ligia Lewis. We collaborated on Levant (2018), a work in which we filmed our three bodies in a dark space. I wore a headlamp on my forehead and Ligia choreographed me and Nkisi as I filmed. There was the attempt to capture images and movement, but also to let the body escape and disappear. This tension between hypervisibility and erasure, or darkness and light, is what I am interested in because something that lacks definition has the possibility for more movement and abstraction. When I speak about Glissant I also think about how he talks about the “abyss” in relation to the Middle Passage, and the idea of a space under us that holds a part of mystery. It is the foundation of what the world is, and the abyss can stare back at the self. I see my work as attempting to use tools to make the invisible visible. I like this failure, this incapacity of representing the invisible. The attempt is an opaque gesture and one of resistance.

LCS: There’s an epistemological interruption, a change in signification, when you move the body from expected spheres into unexpected ones. Seeing your body in an unconventional space is witnessing a person confronting the abyss in real time. This is extremely uncomfortable for those of us who are operating within the norms of physical movement which we have embodied to prevent ourselves from engaging the abyss. In my first book about blackface minstrelsy, I used a term that came back to me when I read critics responding to your work: “naked mask.”2 It refers to how when you reveal something, you’re actually concealing it. That when you are showing your vulnerability, you’re actually masking something.

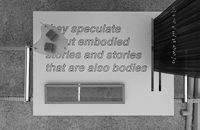

PM: When you are put in a position of performing for an audience, you also need to consider the parameters of the performance to keep a form of agency. The space of performance is no different than the space that we know of as the world. Performance can be dangerous in the sense that everything can be consumed—digested, integrated, but also appropriated. How do you resist this? That’s where I agree with you about the resistance that silence can bring, whether it is a sonic silence or a visual silence. The premise of the exhibition at Mercer Union is grounded in a personal journal. To Be Blindly Hopeful (2023) at Mostyn in Llandudno was the first show where I used and published this vulnerable material for everyone to read. In spite of my own desire to see you disappear follows this project. The journal is still present, but I gave it to Ndobo-emma, a musician based in Montpellier, to read and interpret it as music. We performed together once at the Astrup Fearnley Museum in Oslo, and I was interested in bringing her in on a project where we could collaborate further, especially because her practice is in a realm of more popular music, like neo-soul and R&B.

LCS: The sound piece is very melodic and quite emotionally affective, which, to be honest, is surprising as a sound installation. It’s in conversation with the journal, and in many ways the journal entries are painful. Does working with the style of R&B, which is rooted in heartbreak, failure, desire, and pain, offer you something in a gallery space? Is that the way you convey the affect of the journal? There are also pure sonic moments that activate space in a powerful way.

PM: I’m going to go back to a psychic medium reading I was given, in which I was told that I had the energy of a torch singer. I believe that my work also has this energy. [Laughs]

LCS: Paul, you have nailed it. That makes perfect sense. [Laughs] I come out of reggae and sound system culture, but I’ve retreated from the musical because music is very linked to memory and specific bodily movements. Rhythm and melody are deeply coded, and it’s a way of producing continuity and organizing time and collectivity. But in my sound work I’m interested in what happens if we abandon that. What does sound do for memory without the expected movements and organized methods that draw collectivity and community?

PM: It sounds like your relationship to sound is my relationship to dance, and why I stopped dancing for a while because I needed to reconfigure it. A few years back I asked curators I worked with to not use the terms “blackness” or “queerness” in texts where they wrote about my practice. It comes with a set of expectations and imaginations that are not necessarily connected to my own relationship with my work. I’ve returned to drawings and installation because they allow me to move away from that legibility.

LCS: Music is an interesting metaphor. When you use certain terms (black, queer, immigrant, this, that), they create melodies and familiar rhythms. That’s what shows up in the writing about you and how people consume you. If we are to move from a form of identity politics to somewhere else, I think it has to engage the incredible complexity and confusion— the productive confusion—of blackness. We tend to use blackness as a singular thing because we want to create solidarity. What I find exciting, dangerous, and fueling your work, is how you’re coming to terms with the question: which blackness are we talking about? Tell me more about your relationship to that.

PM: I’m kind of turning my back to the idea of a monoculture around blackness. I think it’s important for me to speak from a specific place, and that’s why I can’t use umbrella terms. My language can be abstract sometimes, but I reclaim it and at the moment I kind of refuse to be in a situation of translation with my work and how I speak about my work. That is also a bit scary for me because it’s much easier to arrive and have a prepackaged discourse around a work. But now I’m trying to move away from that and that’s why the show in Toronto feels so raw. It’s personal, and that’s where I’m leaning towards.

LCS: It might be why after years of producing so much scholarship, two years ago I wrote a memoir in an attempt to ground the work that I do as a scholar and thinker and make sure that it goes back to a specific place. Not because my experience is everyone’s experience, but to make sure that we understand that abstractions come from somewhere.

- Glissant, Édouard. The Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Harbor: University

of Michigan Press, 1997. - Chude-Sokei, Louis. The Last Darky: Bert Williams, Black on Black Minstrelsy, and the Black Diaspora. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

__

Louis Chude-Sokei is a writer and scholar whose works include Race Und

Technologie (2023), Floating in A Most Peculiar Way (2021), The Sound

of Culture (2015), and The Last Darky (2005). He currently advises the

Guggenheim’s Art and Technology Initiative, and is the editor of The Black

Scholar, the leading journal of Black Studies. At the Venice Biennale (2024),

he contributed a sound installation as part of the German Pavilion. He

founded the sonic art/archiving project Echolocution and was a curator of

Carnegie Hall’s Afrofuturism Festival (2022). Notable artistic collaborators

include Mouse on Mars, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company,

Marina Rosenfeld and Mendi & Keith Obadike