This article originally appeared in i-D Magazine, The Radical Issue, no. 351, Spring 2018.

Paul Maheke‘s sparse and compact studio space is in a 19th century church on a quiet backstreet in Tottenham, north London. The house of god is now run by artists, sectioned off with temporary walls but no doors, keeping it open and collaborative for the 20 or so who make work within it. Paul’s section faces out towards a pearlescent glass arched window. It’s hard to imagine how his expansive performative work can be practiced in this small square of space.

Enveloping dance, film and objects, Paul’s practice works together as layers that overlap, vibe, bump up against each other and disrupt. He uses movement, gesture, his voice, light, water, music, bits of text — often quotes from the likes of Audre Lorde and bell hooks, his textual “ghosts” as he calls them — and domestic items. “My work is very much about what’s absent, what’s left untold, what’s left unseen,” he says. Race and gender are central to Paul’s work, not in the sense that he addresses them as subjects. Rather they are, as he describes, modes of production. “My work is not about Blackness or Queerness, but rather is queer and black,” Paul texts later, as we continue talking after our studio visit.

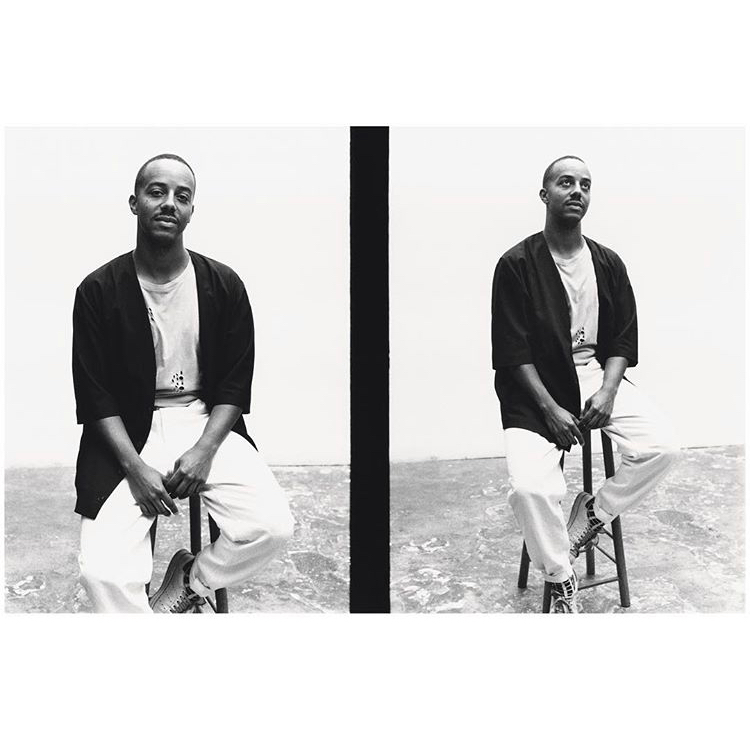

The artist is warm, unassuming, has an easy smile, is generous with his time. The day before we meet up, he gives a lecture at the UCL Slade School of Fine Art about his work, then dutifully answers all questions as straightforwardly as possibly — difficult because his art embodies complex ideas. Paul says the word “somehow” the way people use “like”, as a linguistic filler, which is really charming and likely a result of looking for the right words in English, rather than his native French. He grew up in Paris, where he studied art for 7 years. As his interest in Black feminism deepened, he had found it hard there. “At the time it was really the beginning of the democratisation of gender studies in France. And people were really reluctant to it,” says Paul. Increasingly he felt he didn’t belong — and wanted something else. After a few years in Montreal, a friend told Paul about the Open School East, then in Hackney. After applying and getting in, he relocated to London and things quickly picked up. Paul’s art started really resonating. He landed the South London Gallery Post-Graduate Residency in 2015, culminating with an exhibition there the following year. The success of it took him by surprise. “This is something a bit weird to say, but I really never thought that my work would interest anyone, honestly, I’m not trying to be like…” he says, trailing off to mime false modesty. He imagined the show was for his friends, had no expectations. “But then the response was really amazing.”

Working with experience and space, Paul’s art conceptualises the body as a container of history and meaning. “For queer people of colour there is this huge imbalance between those moments of erasure and absolute invisibility, and simultaneously there is an hyper-visibility and a demand for that, and how do you navigate that.” He’s seeking to rearticulate, destabilising dominant narratives. « There is something that has to, for me, go beyond the representational because the representational is also violent.” He is creating space for understanding identity beyond colonialist, hierarchical frameworks. To make room for discussion. “There is this idea of placing myself somewhere outside — believing in the position at the periphery of things, and the periphery can address the centre by staying at the periphery.”

— Clem de Pressigny