WHEN MBU, 2017, PREMIERED LAST SPRING at Tate Modern, it was difficult to actually see Paul Maheke dancing. His body was obscured and occasionally illuminated by video projections and layers of hanging scrims. Past the initial frustration, these impediments to spectatorship, it became clear, were as much part of the piece as any of Maheke’s choreography. Viewers were unable to hold him in sight for long. The effect was to make the dance feel ambient rather than spectacular, something best enjoyed with the same etiquette as that of the dance floor: by casting the occasional obliquely held glance. Mbu isn’t the only one of Maheke’s works that establishes this kind of fitful, flickering visibility: In his 2016 exhibition “I Lost Track of the Swarm” at South London Gallery, for instance, a three-channel video showed him dancing with a light attached to his waist, held in his hand, or positioned behind him, instigating a disorienting play of shadows.

While Maheke’s earlier solo work confronted the audience with queer anxieties around masculinity by appropriating dance forms born in strip clubs, Mbu held the atmospheric tension of a family affair. Titled after a word for ocean in the Bantu dialect spoken by the artist’s Congolese father, the piece threaded together deconstructed dances from the globally dispersed cultural and subcultural heritage of Africans. Set to live drumming with club beats over which the artist’s father sang, it gave the audience a glimpse of a black internationalist social dance concerned neither with virtuosity nor any polemical rejection of it. Dressed informally in exercise clothes, Maheke sought good movements, hit on them, and refreshed their concepts, resting as needed.

Less a solo than a rehearsal for a night out, Mbu featured Maheke’s characteristic repetition of pared-down gestures that neither alienated nor immersed the audience but, true to the performance’s namesake, swept them along; this effect was heightened by the driving, hypnotic bass that accompanies many of his recent projects. Offering up the pleasures of black popular culture, Maheke also holds viewers at a distance by formally incorporating the critical discourses that are the works’ conditions of possibility. Dislocated fragments from feminist and postcolonial theory, printed, spoken, or projected, are among Maheke’s artistic materials, the constant accompaniment to his dances.

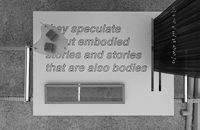

The work’s affirmative tendencies—the celebration of queer social life and the sidelong citation of political self-care—were elevated and punctured when the words the problem was that we didn’t know whom we meant when we were saying we cropped up on a scrim hanging over the artist, framing his thrashing to the drums below. Threatening to undermine the whole business of familial and subcultural identification, this provocative and troubling line turns up time and again in Maheke’s sculptures and performances. In “I Lost Track of the Swarm,” it adorned diaphanous curtains that hung from the ceiling, blunting the room’s hard edges. Wherever it appears, it expresses Maheke’s heretical devotion to the “politics of location” put forth by Adrienne Rich. In her 1984 essay “Notes Toward a Politics of Location,” that rubric had announced her conflicted commitment to, and the necessity of her departure from, a strain of Western Marxism whose “revolutionary universal subject” seemed more reification than reality. In this context, she proposed a moratorium on the phrase “the body.” Henceforward, “my body,” singular and possessive, would be the horizon of locative politics.

Maheke’s practice has developed in active response, he says, to the ways in which performances done inside art institutions tend to amplify the violence that subtends institutionality. And the impoverishment of the discourse through which so much black art is filtered has driven his social criticism to the surface. The intellectuals who inspire the art receive explicit citation, as the works themselves respond to and fulfill the need to produce the intellectual conditions necessary for their adequate reception.

Critical distance and visual obscurity are two tactics of slow, strategic withdrawal. Like many Conceptual artists before him, Maheke began his career with anonymous public interventions and developed more manifestly social content over time. His early works were delightful objects of minor spectacle: little monochromes left as gifts in strangers’ parking spots, or small reflective shapes installed outside to catch the sun just so. But on his moving from France, where he grew up, to London in 2015 to study at Open School East, the social concerns latent in his work erupted.

Wary of art’s renewed turn to “community,” but interested in the actual community groups of East London with whom his school shared a building, Maheke produced the two-channel video installation Mutual Survival, Lorde’s Manifesto, 2015, recording the women of the Tropical Isles Carnival Dance Troupe as they rehearsed in a Hackney basement and captioning the footage with words from Audre Lorde. The verité-style camerawork charged the images with a feeling of illicit documentary, confirming the dance class as a form of community self-defense. For Maheke, dance has been the bridge from work addressed to an anonymous public, made by no one in particular for strangers and passersby, to the locative political commitments that take Rich’s concern to heart. But it is not only as an act of humility that Maheke won’t call himself a dancer; it may also be another kind of withdrawal. For a forthcoming solo exhibition at Chisenhale Gallery, London, he has made the decision to refrain from live performance: He will choreograph the movements but not enact them. The infamous condition of the medium, the impossibility of distinguishing the dancer from the dance, has proven the ideal situation though which to attend to the limits of Rich’s still-urgent prohibition. In each and every performance, whether absent or present, Maheke improvises on the unsettled ground where absolute generality (“we”) and total individuation (“my body”) meet in vexed convergence.

Artforum, April 2018