Chisenhale Interviews: Paul Maheke

A fire circle for a public hearing 13 April – 10 June, 2018

Ellen Greig: Let’s start by discussing what visitors’ experience when they first enter the space: you have removed the gallery doors and in the entrance of the exhibition space you have installed a black curtain that leads you to a large mural that occupies the whole wall. Can you talk about this first experience of the show?

Paul Maheke: I was keen to construct the show in a way that would offer different perspectives of each work within the exhibition. The installation provides multiple sightlines. Through the use of the heavy curtains that are installed throughout the space, I hope to play with what is immediately visible and what is not so visible.

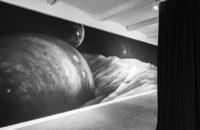

So, upon entering the space you are met with a curtain that obstructs your view and directs you to a large mural of a cosmic landscape. This mural has been painted directly onto the wall, and includes the planet Jupiter surrounded by cosmic fog, planets and stars. The mural is painted in a style that takes from sci-fi and fantasy imagery. I’m interested in the significance, and the clichés, of speculative belief systems, such as cosmology and astrology.

EG: Why have you chosen the planet Jupiter?

PM: In Astrology, Jupiter is the planet of knowledge, abundance and growth. The planet is very physically complex; it is full of enormous storms of gas and different types of matter and it is one of the biggest planets in our solar system. Within this exhibition, I see Jupiter as an allegory to think about how knowledge can translate into material form.

One aspect of the exhibition is a performance that is not always visible, but it is always present. For me, Jupiter’s inclusion in the installation responds directly to the character of the Oracle, embodied by one of the performers, Heather Agyepong, who says at one point in Part 1 of the performance: “I am the lived and experienced knowledge”.

EG: Each element of the work references and pulls directly from specific pre-existing material. Why have you chosen to work in this way?

PM: I wanted to incorporate various elements within the exhibition that encounter and connect to each other, but also branch off, which, for me, begins to complicate the discussion around identity, representation and bodies. I was interested in rearticulating pre-existing material, to re-work it for a present moment. It is important that I found the right way to reintroduce certain iconic and historic artworks and references into my own work in a way that would both celebrate and actualise the political relevance of these references. For example, in the performative element of this exhibition I have asked one of the performers, Titilayo Adebayo, to incorporate gestures from Bruce Nauman’s film and performance work,Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square (1967) and Felix Gonzalez Torres’ performance, Untitled (Go-Go Dancing Platform) (1991) into her character, who is a possessed drag king.

Titilayo utilises the femme, the masculine and what is in-between, in both her work as an artist as well as in her life, so she really is the perfect person to enact the character of a possessed drag king. This character jumps in and out of many personas, referencing Gonzalez Torres and Nauman, to Michael Jackson and Eisa Jocson and her Macho Dancing work; a work that has turned into a screen for many projections and fictions. Titilayo’s re-working of Nauman’s piece in this exhibition relates to masculinity, performativity and body policing. The use of Nauman’s work here also links to Michael Jackson’s use of walking in his choreographic work, which I feel disrupted some misrepresentations or tropes attached to Black masculinity. Michael Jackson is another continuous reference in the performance.

EG: How have you approached choreographing this new performance work?

PM: The performances are divided in three parts, and each part looks at a form of speech, or a form of movement, or way of occupying space. I have written a script for each Part, all of which incorporate aspects of spoken word, song, dance and movement. For example, Part 1: I took everything and made it my own (the ghost and the appropriationist) runs from the opening to the 29 April, with daily performances at 3pm everyday the gallery is open. Part 1’s choreography borrows from the language of theatre – using spoken word, tap dance and direct engagement with the audience. It includes all three performers, Titilayo Adebayo, Heather Agyepong and Carrie Topley. Part 2 and 3 develop new choreographies that will be performed at 3pm everyday the gallery is open.

I have written a script that has become the foundation for the choreography. The script borrows from many authors such as Édouard Glissant, Audre Lorde, Judith Butler, and Sylvia Wynter to Grace Jones lyrics, among other references. I have also included some of my own texts in the script. I revealed to the performers yesterday that part of the script is taken from a very personal letter I sent to an ex-boyfriend. The script reads like poetry in the way that the text weaves together, making the performance as seamless as possible, so that it comes across as a single narrative or block, but it is made of heterogeneous elements.

EG: Why have you chosen the format of a three-part choreography that takes place throughout this nine-week exhibition?

PM: I’ve chosen to work with this format, as I wanted to explore different modes of address and different forms of performance practice within the exhibition timeframe. I have tried to develop the performance so that it disrupts and resists a linear narrative. The performance element of the work is more like a shattered narrative that explodes in many directions. It’s almost trying to find another dimension to the show through the fact that it is varied and manifold, and that there are multiple voices. Each performer embodies multiple characters across the duration of the exhibition.

EG: So, for example, could the first part of the performance come at the end and the second part come at the start?

PM: Exactly. There is no chronology, no narrative arc to the three parts. Each part is like a different ‘state’, which could expand, change and reshape in future iterations. For me, it is really important for people to approach the exhibition in different ways and have the potential to come and see another version of the performance at differing times. Visitors will also experience the installation without the presence of performers. I’m interested in how to create a space that is continuously performing, but might not always involve a physical presence.

EG: Could you talk about how this exhibition explores structures and systems that produce both visibility and erasure?

PM: I am interested in multiplicity and overlay – multiple logics that may clash. In my work, there is always a part of me that is interested in abstracting bodies, ideas and references. In the process of abstracting, I feel there is something that references an understanding of queerness and blackness as modes of production. Through this exhibition I hope to explore a tension between moments of erasure and hypervisibility, and the seemingly impossibility of escaping this pattern when black and queer in the West.

I am conscious of queer artists of colour often becoming a screen of projection. I feel you are asked to take on board all the non-white issues and all the non-straight issues; you become the voice of the oppressed. You are supposed to address gentrification, Brexit and social violence etc… People often don’t realise that being here—and making yourself visible—is enough to put you at risk.

EG: In this exhibition you’ve chosen not to perform live, but your body is still present through a video work that is on a continuous loop.

PM: In the video, which I made in the Dominican Republic whilst on residence there recently, I’m dancing underneath a camera, which is attached to a moving fan. So, the video is shot from above and with the rotation of the fan my body is abstracted and transformed. I was interested this very simple, very DIY process, which creates a very hypnotic image that is hard to read because it is quite dizzying.

The image of me performing to camera is one consistent within the exhibition. I am one of the many voices behind the show. The way that I have worked with the performers was very much a dialogue, and elements of the performers own artistic practices are included in the work. They are all jumping in and out of a character. I am the only one who is not embodying someone other than myself.

EG: Your use of cinematography and editing obstructs your full presence. You are always there, but not always fully visible. In the same way that the performer’s characters are always present in the exhibition, but not always visible.

PM: You’re right. Also, my body sometimes transforms into a shape that is not recognisable as a human figure.

EG: Can you say something about the figure of the ghost that you reference in this new body of work?

PM: For me, the ghost is a cornerstone to articulate a lot of what I am trying to do here with the exhibition. I see the idea of a ghost as a resilient figure that occupies several dimensions. It has an ability to make itself visible or not. It represents a memory from the past that may, or may not, manifest in the present, yet lingers in a timeless and unallocated space. It haunts.

The ghost also connects different kind of imaginations, which break with a linear understanding of time and history; it occupies several dimensions. It is both celestial and vernacular.

It also seems to respond to an ever-present concern in my work, which is related to abstracting bodies and identities.

For me, it is a useful figure to think through identity outside of ‘identity politics’. I feel this need to twist representation and work from representation and beyond, thinking about the body without attaching physicality to it. The ghost has some affiliated figures as well, like the magician, the oracle, the possessed, and the medium, which all play a role in the development of the performance work. For example, in Part 1 of the performance, The Oracle is speaking about being this empty space or cavity that has no visible existence. In relation to humanity, how does it translate to our histories as humans?

EG: You have worked with artist Sophie Mallet to develop a sound piece for the exhibition. Can you talk about the sound component? PM: The sound work acts as the soundtrack to the whole exhibition. Sophie and I worked in close dialogue on the development of the work. I shared references, images and sounds with her that influenced the direction of the work. We then shared ideas about a compositional structure that would reflect this idea of the presence of the ghost – again the idea of circularity and the alternation between appearance and disappearance was an influence here. Sophie then developed a looped sound work that suggests a cinematic score. It tells a story. She also included recordings from the performers reciting part of the script within the sound work, so there will be a presence of their voices in the space, even when they are physically absent.

EG: You mentioned the Dominican Republic before. You spent quite a lot of the production period of this exhibition whilst on residency there.

PM: The Dominican Republic, moreover the Caribbean, has always been an archipelago that I have been interested in – from the multiplicity of cultures to the painful history. I also feel there is a potential for reinvention and how, from those very painful histories, beautiful things have emerged, without erasing the difficulties.

In this exhibition, I am exploring the idea of a territory as a space for reinvention and rearticulation, and the exhibition space somehow being a reflection of that. Making the presence of the ghost very central to the work came from the fact that the residency is set up in a site that has many layers of history, and also many ghost stories! I met with a medium and a psychic while I was there, which has nourished this new work because I feel it is also a way to articulate emotions and trauma in a different way.

I met with one medium who is queer, which felt important at the time. It’s funny because the reading happened at the end of the residency, just a week before we started installing. The reading completely shed a new light on the performance and helped me understand what I was doing, and to trust my intuition. It was almost as if the work preceded me.

The show takes many heterogeneous elements that connect together in a non-hierarchical way within the exhibition format. When they are put together, and I am in the space, then everything starts to connect. That is why I am interested in the format of the exhibition – the space where meaning is revealed. The work has an agency, and the work only translates for me when the exhibition is put together. That is why it is hard for me to dissociate the objects from one another. They are all interconnected.

EG: You are sampling and then creating your own narrative and form.

PM: Totally. It’s a cosmology in itself. It’s a world taking shape in front of an audience. That’s maybe what connects the show so much to theatre. It’s an ever shape-shifting space.

Interviewed by Ellen Greig, Curator: Commissions, Chisenhale Gallery, on Friday 6 April 2018 at Chisenhale Gallery, London. Chisenhale Interviews, series editor, Polly Staple, Director, Chisenhale Gallery.

PDF here: Paul Maheke and Ellen Greig (Chisenhale Gallery) in conversation