Paul Maheke, Taboo Durag, 2021. Performance documentation at the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago. Images courtesy of the the Renaissance Society. Photos by Meg Noe.

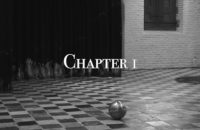

A pair of sneakers and a durag—singular ornaments resting at the edge of a lone spotlight—carry an auratic weight even before dance artist Paul Maheke dons them in his recent performance, Taboo Durag (2021). These objects offer a seat for our attention and anticipation, as we make our way through the surrounding darkness, gathering on the gallery floor around the illuminated circle.

When Maheke quietly enters the Renaissance Society’s yawning space, at the University of Chicago, he wears protective padding over his knees, though his feet are covered only with socks. Arriving in the spotlight, Maheke begins slowly to move: a soft tremble in the knees initiates a prolonged sequence of quivers and tremors that bring the body into slightly bounding rotations. A soundscape of gently keening voices fills the space as the dancer shakily spirals, eventually opening his own mouth to add to the chorus. The bodily vibrations amplify, sending arms surging out and making downcast eyes tentatively float upward. Eventually, one hand reaches toward his hair, and Maheke steps out of his tight orbit. Now is when he makes his way to where his two items sit, slipping his feet into the shoes and crouching to lace them.

Queer choreographies often activate the potency of otherwise commonplace accoutrements. Andrew Tay’s Monsters, Angels and Aliens are Not a Substitute for Spirituality (2014) presents audience members with talismans made from cheap baubles and plasticy bits. These are willfully tacky assemblages proffered to amplify desire and spectatorial relation. Some works in Trajal Harrell’s Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at the Judson Church (2009-2017) series feature racks of clothing, textiles, and accessories that performers use to generate a cavalcade of personas and characters. Composing with leather gloves, macarmé, blankets, and scarves, the dancers observe a lesson from vogue ball runways: the power of a good prop. In Taboo Durag, Maheke’s objects both amplify and compose his exertion. But even more, they give him the protection to endure it.

Especially on the gallery’s concrete floors, to continue dancing without shoes would be uncomfortable, even painful. Meanwhile, the durag begins by mimicking what it typically covers and maintains. Placing the object onto his head, Maheke leaves its strings hanging down, untied. As if tossing lush tresses of hair, Maheke repeatedly flings the pendulous limbs of fabric backward while turning to look coyly over each shoulder. Soon, his recorded speaking voice, which accompanies most of the work, describes letting “my hair grow big in the hope that it would keep you away.” Maheke pulls his durag strings outward, creating tensile lines that trace a circumference, a buffer, around the body. Such simple motions toward corporeal safeguarding draw a counterpoint to the transgression that occupies the conceptual and affective center of Taboo Durag.

Buffering the body, too, are the compounding meanings of the dancer’s movements. When Maheke’s voice references the “unresolved dead,” it might be easy to see the thrust of his aligned fists as illustrative, shoveling into earth to find resolution, whether in burial or exhumation. Yet there is too much loose momentum in his motion for this to be quite right—it’s a spearing more than a digging, and then it’s something like the waving of a flag as Maheke lifts his hands.

Maheke’s props are equally motile in their signification. The durag is a crown, as the photographer John Edmonds interprets it in a 2017 series of pictures.1 It can be a memory of family: Lauretta Charlton relates how Edmonds “remembered his mother wearing do-rags when he was a child.” In adulthood, durags become, for Edmonds, “performative gestures of black masculinity” and “symbols of self-styled beauty.” Matthew Draughter’s poem “Celestial-: On the Topic of Unloving” (2020) puts it this way: “pressed between a rock and masculinity / is the hard place / you keep reading me / this boy feels like unpacking / a new durag and finding a new way to lay my edges down.”2 And in Danez Smith’s poem “summer, somewhere” (2017), this object grants renewal even amidst ongoing state violence: “we give him a durag, a bowl, a second chance.”3

Maheke finally finishes tying his durag while seated on the floor, flexing and stretching his ankles to push his body in a slow revolution. This activity melds into a sequence that sees the dancer extend an arm, tracing a circle with a closed hand. Maheke repeats the motion, switching from arm to arm, as if turning a car’s steering wheel, and the action’s momentum helps him come to his knees—and then to a deep, weighted crouching. Like Maheke’s durag, this gestural unit might conjure a performance of masculinity, with a downturned chin, low slung posture, and cavalier lean. More importantly, it allows the dancer to turn his gaze emphatically to the audience, in contrast to earlier moments when Maheke keeps his eyes focused downward with a mien of inward concentration. Even in their closely calibrated deployment, Taboo Durag’s movement vocabularies and material components slip swiftly among multiple visual and semantic associations.

The somatic focus and referential oscillations of Maheke’s choreography make Taboo Durag’s arrival at verbal immediacy all the more wrenching. Tension and unease ripple throughout. Maheke’s monologue alludes to harm enacted by a loved one, by the “you” of his address. He notes his feeling of sadness “beyond what’s respectable” and describes “the invisible nature of what happened to me.” In one section of the work, Maheke brings a fist to the side of his cheek, and the undulations of pressure that build at the surface where hand and face meet invoke some threat. Yet it is not until the work’s final moments, as Maheke exits leaving only his voice, that the violation he gestures at is named: “A void full to the brim with its own gravity. A celestial hole that swallows. I had been raped but I didn’t know. I didn’t compute it. Only he knew, only you knew.”

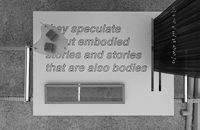

Moving between self-protection and testimony, Maheke’s compositional choices work through a bind also explored in recent works theorizing how to address scenes of “anti-Black, ableist, racist, and anti-trans/queer” harm. Eric A. Stanley’s Atmospheres of Violence, released last fall, reflects on the exigencies that attend reproducing narratives from “a wicked archive of murders, the ongoing HIV/AIDS pandemic, suicide notes, incarceration, police video footage, and other ephemera of attack.”4 “These imperfect decisions,” they explain in a prefatory note, “are guided by a radical commitment to keeping each other alive and toward ending the world that produces this unfolding archive.”5

The violence Maheke has experienced is intimately interpersonal, but joins this painful catalogue. And his choice to name his experience of violence freights Taboo Durag with the concreteness of fact, even if it arrives, as trauma according to convention does, belatedly. “Rape, raped, fixed,” intones Maheke’s voice, with a simple finality that belies his larger investment in repetition, recursiveness, and ambivalence. Contrary to such a past tense assertion, the final moments of Taboo Durag uncomfortably intumesce. So much of Maheke’s piece—with its gently beseeching spins and restless shaking—feels like an embodied process of working through a barbed thing that’s snagged or stuck. The performance’s conclusion emphasizes that this labor of surviving trauma is both ongoing, and shared.

Stanley asks, “How might we enter into these scenes as a praxis of care, as an exercise of solidarity, when the very possibility of ethics has already been destroyed?”6 Maheke’s performance provides one possible approach: advance an open-ended reciprocity. Taboo Durag’s porously signifying composition offers an invitation to those looking on. The resonance of the dancer’s recorded voice throughout the gallery unsettles the division between the illuminated space of his work and the darkened space of our own. Put plainly, if Maheke is here to work out some pain, maybe even to grieve, his piece is generous enough to allow us to use the room similarly. Like the molten vowel sounds that yoke the two terms of its title in oozing chiasmus, Taboo Durag suggests we might hitch a little grieving of our own to what the dancer does.

“Because you were inside me, I had to be around you.”

Amid the sting of Taboo Durag’s final utterance, the prepositions “in” and “around” dilate onto something else. Not a resolution, not something “after.” But for a brief time, Maheke lets us be in and around the work, with one another. And for this moment, that is enough.

original review published on ASAP Journal on 28 April 2022

Endnotes

- Lauretta Charlton, “John Edmonds’s Luminous Images of Men in Do-Rags,” The New Yorker, March 18, 2017. www.newyorker.com/culture/photo-booth/john-edmondss-luminous-images-of-men-in-do-rags.

- Matthew Draughter, “Celestial-: On the Topic of Unloving,” The American Poetry Review 49, no. 4 (2020): 35.

- Danez Smith, “From ‘summer, somewhere,’” Poetry, January, 2016. www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/58645/from-summer-somewhere.

- Eric A. Stanley, Atmospheres of Violence: Structuring Antagonism and the Trans/Queer Ungovernable (Durhamn and London: Duke University Press, 2021), 5.

- Ibid, ix.

- Ibid, 15.

_

Fabien Maltais-Bayda’s writing can be found in ASAP/J, C Magazine, Canadian Art, Canadian Theatre Review, The Dance Current, esse, and Momus. He has also written and translated for the anthology Curating Live Arts (Berghahn Books, 2018), and contributed texts to publications from the Art Gallery of York University and Blackwood Gallery. He is a PhD student in English and Theater and Performance Studies at the University of Chicago, and a non-fiction staff member with the Chicago Review.